What Nouriel Roubini Will Not Tell You about the US Economy

My associates at Action Economics take on the emerging bearish consensus:

Despite the market’s nearly uniform belief that a significant economic “slowdown” is underway, today’s retail sales, trade price, and inventory data join our reference yesterday to the litany of indicators that are refusing to cooperate with the consensus view.

For the record, we are seeing virtually no signs of a slowdown in consumer spending as we enter the second month of Q3, As gauged by today’s retail sales report as well as nearly all the consumer confidence and income statistics. The surge in July tax receipts revealed late yesterday, combined with the solid growth trajectory of hours-worked through the month from last Friday’s payroll report, ensures that income posted another round of solid growth on the month.

In addition, all the major factory sector indicators suggest continued solid growth in this bellwether sector, and industrial production to be released next Wednesday will reveal a big 0.6% July gain that follows the even bigger 0.8% June increase. In addition, as noted yesterday, both exports and imports entered Q3 on a robust growth path as signaled in the June trade report. And, the construction sector is continuing to post solid growth despite housing sector fears thanks to a booming commercial and public sector, as signaled by continued strength in building material prices, alongside steady 9%-13% y/y growth in sales of building materials that received a big boost from the 1.8% July sales surge. Inventories posted solid gains through Q2, though the ratio of inventories to sales remains remarkably lean.

We continue to believe that economic growth is moderating in these middle years of the expansion by about 0.5 percentage points, from a 3.7% clip over the last thirteen quarters to about a 3.2% rate, as Fed policy moves to neutral from accommodative. But this slowdown in real growth will be hard to see in many of the volatile monthly reports that the markets watch, and larger price gains in the second half of the expansion may diminish the effects of this moderation on the reports that are not inflation adjusted, like retail sales, or inventories.

For today’s data, note that retail sales grew at a solid 7.6% rate in Q2 despite a market focus on the “draining” effect of surging gasoline prices on the “real” spending component in the last quarter, which is an “above trend” growth clip despite notions in the market that the slowdown began with the consumer in Q2. In Q3, retail sales are on track to grow at a 7% rate, and with less of the gasoline “drain” on the real figures that will leave real consumption growing at a 3.3% Q3 rate that is right in line with our 3.0% Q3 GDP forecast.

posted on 12 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Unit Labour Costs and Inflation: Alan Reynolds Takes on Some Old Friends

Alan Reynolds on that recent WSJ editorial:

That editorial rebukes the Fed for drifting “back to the era of the Phillips Curve,” which blamed inflation on “wage push” resulting from low unemployment. Yet the same editorial enthusiastically embraced the Phillips Curve, fretting that “unit labor costs are now 3.2 percent higher than a year ago; that’s the fastest increase since 2000, when monetary policy was considerably tighter than it is now.”…

The Phillips Curve notion that increases in unit labor costs predict or cause higher inflation was debunked in studies from the Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond (Yash Mehra), Dallas (Kenneth Emery and Chich-Ping Chang) and Cleveland. The latter paper, by Gregory Hess and Mark Schweitzer, found “little systematic evidence that ... unit labor costs are helpful for predicting inflation.”

A March 2005 study for the Bureau of Labor Statistics by Anirvan Banerji found that “upturns in unit labor cost growth actually lag upturns in CPI inflation 80 percent of the time.”

The Fed is right this time, for a change. I regret to say that their toughest critics, including many of my oldest and best friends, are wrong.

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s model of inflation is a mark-up model based in part on unit labour costs. The RBA are the first to concede that the data reject their model. They impose it anyway and ask if it predicts inflation. It does, which makes this approach defensible, but still not very satisfying.

posted on 11 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

RBA Rate Hike Probabilities: Are Census Workers Like Bananas?

RBA rate hike probabilities implied by 30 day inter-bank futures have surged after yet another strong employment report that sent the unemployment rate to new multi-decade lows of 4.8% in July. Early employment of Census workers probably contributed to the increase in employment in July, with another 10,000 addition to employment from the Census likely in August. Of course Census workers are no more to blame for higher interest rates than bananas.

Every three months, the Australian and New Zealand employment reports coincide. The two reports show the price Australia pays for a less liberal approach to labour market reform, with NZ’s unemployment rate re-visiting the record lows from last year at 3.6% in the June quarter. NZ also has an official cash rate of 7.25% compared to Australia’s 6.0%. This underscores a point we made previously: the sort of economic growth that drives unemployment rates to multi-decade lows is not going to give you low interest rates. Higher interest rates reflect good economic news, not bad.

By the way, weren’t Australia and NZ supposed to be in some sort of currency and financial crisis by now? Yet another failed Roubini forecast.

posted on 10 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Bernanke & Inflation

The WSJ, channelling gold bugs and fever swamp Austrians, frets over the August Fed pause:

Mr. Bernanke no doubt hopes that yesterday’s pause is one that refreshes; we fear it has only postponed the ultimate day of reckoning.

James Hamilton instead offers a timely warning:

There are those who will doubtless never surrender their conviction that Ben Bernanke is in reality a bird, with the latest FOMC statement confirming him as a member of the family Columbidae. To those pundits I repeat my previous warning—if you invest based on that misunderstanding of Bernanke, you’re going to get whacked down by reality.

posted on 09 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Dr Strangelove of Global Macro, Part II

Nouriel Roubini has engaged in a furious linking frenzy over at Doomsday Cult Central in support of his US recession call. Nouriel seems oblivious to the paradox that makes recession forecasting so difficult. Recessions are inherently difficult to predict, because if they could be forecast with reasonably accuracy, policymakers would take action to avert them and the public would change their behaviour in ways that would mitigate their effects. The news and data flow that Nouriel points to in support of his recession call is the same information that the Fed will be responding to when it (more than likely) decides to pause its tightening cycle in August. Nouriel now acknowledges this possibility in his latest post, but argues that a new Fed easing cycle will be too little, too late to avert recession.

All this conveniently ignores the fact that Nouriel has been prominent in arguing that monetary policy should respond to asset price ‘bubbles,’ particularly the supposed US housing ‘bubble.’ If the Fed had taken Nouriel’s advice, US interest rates would presumably be even higher than they are now, greatly increasing the risk of the recession Nouriel claims is now imminent. Indeed, the central bank that has most explicitly targeted house prices in its official explanation of policy, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, had a narrow brush with recession in the second half of 2005.

Nouriel is not alone in trying to have his monetary policy cake and eat it too. Even conservative commentators who should know better, like Des Lachman of the AEI, have sought to argue that the Fed both failed to ease quickly enough in the wake of the tech ‘bubble’ and then eased too much to prevent the housing ‘bubble.’ Lachman and Roubini are effectively claiming that they know of some alternative path for Fed policy that would have better smoothed both asset prices and the real economy, leading to better macro outcomes. This is nothing but after the fact hubris. Adam Posen has presented a definitive debunking of Nouriel’s arguments in favour of central banks targeting asset prices. I make similar arguments here against those who argue that the Fed could and should have prevented the US tech ‘bubble’ of the late 1990s.

Nouriel was spectacularly wrong in his structural bear call on the US dollar in 2005, not because the USD failed to collapse as he predicted, but because even if it had, it would have had none of the consequences he predicted (remember that this too was meant to have caused a recession!) It is not enough simply to be a permabear and then wait for the cycle to finally deliver vindication. You have to be right for the right reasons.

posted on 06 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The RBA’s Non-Statement on Monetary Policy

Once every three months, financial markets turn to the RBA’s quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy for guidance on the monetary policy outlook. More often than not, they are disappointed. It’s not hard to see why. The quarterly Statements are scheduled after the Board meeting that follows each quarterly CPI release, so they typically serve as vehicles for the ex post rationalisation of existing policy moves, while studiously avoiding any explicit discussion of the policy outlook. The broad-brush inflation forecasts contained in the Statements have taken on an increasingly endogenous character, being left largely unchanged from one Statement to the next because of intervening policy moves. It is unlikely that the RBA would forecast underlying inflation outside the target range, since this would beg the question as to why policy action had not already been taken to pre-empt it. The Bank would essentially be admitting that it was in the process of making a policy error.

Instead of persisting with the fiction that inflation is an exogenous variable, the RBA should move to formally endogenise its forecasting process to a published projection for the official cash rate that it believes is likely to be consistent with maintaining inflation within the target range. This would help ensure the credibility of its medium-term inflation target, by making it more explicit that inflation is not an exogenous variable under an inflation targeting regime, as well as giving clearer guidance on the monetary policy outlook.

posted on 04 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Do You Really Want Lower Interest Rates?

The government’s claim that it can keep the level of interest rates lower than the opposition Labor Party may have been an effective line at the last federal election. The downside is that it makes it harder for the government to then turn around and disassociate itself from interest rate outcomes in the midst of a tightening cycle. In the short-run, interest rate determination has very little to do with anything the government does (within reasonable bounds) and the policy differences between the two major parties are certainly not large enough to have a significant influence on interest rate outcomes.

Interest rates can be expected to cycle around their long-run equilibrium real rate. This long-run real rate is determined by structural factors, such as productivity growth and the real rate of return on capital. We are conditioned to think of higher real interest rates as being bad for economic growth, but this is true only in a narrow cyclical sense. The long-run real rate is determined by the real rate of return on invested capital and we want this rate to be higher, not lower. Countries like Australia and New Zealand have higher interest rates than found in many other industrialised countries in part because their growth prospects are relatively stronger (it is also why they have relatively large current account deficits). High real interest rates and current account deficits are symptomatic of economic strength, not weakness.

The country that has been most successful in keeping interest rates low in recent years has been Japan, which achieved this dubious distinction by saving too much, over-capitalising its economy and trashing the real rate of return on invested capital. Not coincidentally, Japan also runs a current account surplus.

posted on 01 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Dr Strangelove of Global Macro

It doesn’t take much to get Nouriel Roubini excited these days. US Q2 GDP falls short of expectations, and Nouriel starts salivating over the prospect that the cycle might finally validate his years of perverse doom-mongering:

this Q2 GDP report is as bad as it could be. I thus stick with my prediction that, by Q4, the growth rate will be close to zero and by early 2007 the U.S. will be in a recession. Panglossian optimists have been proven wrong again. They’d better start adjusting their wishful-thinking forecasts of H2 growth (still close to a 3% consensus) to a reality of an economy rapidly slipping into an [sic] nasty recession.

Nouriel is nothing if not thorough in his bearishness. If Nouriel is to be believed, not a single asset class or region will be spared:

In 2006 cash is king and all risky assets (equities, EM bonds, currencies and equities, commodities, credit risks and premia) will be battered once the markets finally comes [sic] to the realization that a U.S. recession followed by a serious global slowdown is coming.

Finally the other delusion in the market is that, even if the U.S. were to slow down, the rest of the world (EU, Asia, China, Japan, Emerging Markets) will be able to “decouple” from the U.S. slowdown and keep on growing perkily…quite simply, when the U.S. sneezes the rest of the world gets the cold. The decoupling fairy tale will be proven as wrong as the U.S. soft landing Panglossian fairy tale.

So Nouriel pretty much has all bases covered for anything that might go wrong anywhere in the world for the foreseeable future.

posted on 29 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Random Walk Down Martin Place

Vanguard Australia is presenting a seminar by Dr Burton G. Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, and Chemical Bank Chairman’s Professor of Economics at Princeton University, 17 August at the Westin Hotel, Martin Place, Sydney. The topic for the seminar, not surprisingly given the sponsor, is ‘Why It Pays to Invest in Index Funds.’

You can register here.

posted on 28 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Yes, We Have No Bananas: Anatomy of an Inflation Shock

The 1.6% quarterly and 4% through the year increase in the CPI in the June quarter will be seen cementing the case for an interest rate increase from the RBA next week.

In reality, the headline June quarter inflation number will have little to do with the reason the RBA is likely to raise interest rates. Petrol and fruit prices together contributed one percentage point to the headline increase over the quarter, with a 250% Cyclone Larry-induced increase in banana prices the main culprit in higher fruit prices. Strip out volatile and non-market determined prices and the CPI rose a more subdued 0.6% q/q and 2% y/y.

What is likely to concern the RBA is the firming trend in the various measures of underlying inflation, at a time when its medium-term inflation forecast is already near the top of its 2-3% target range. The continued run of strong activity data, including the probability the unemployment rate will post new near 30 year lows in the months ahead suggests further upside risks to the RBA’s inflation forecast.

What should concern the RBA even more is that its inflation target appears to have lost credibility with the bond market. Yields on inflation-linked Treasury bonds have implied an inflation rate above 3% since December 2005, with the implied 10 year inflation rate having risen steadily from 1.9% back in June 2003 amid the global deflation scare of that year. With the exception of the uncertainties surrounding the introduction of the GST in 2000, this is the first time the implied inflation rate has been above the inflation target range since 1997.

posted on 26 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

Demographic Change and Asset Prices

This year’s RBA conference volume is up in draft form. This year’s conference looked at:

the impact of demographic trends on macroeconomic factors relevant to financial markets, particularly saving and investment, capital flows and asset prices, as well as on the structure and operation of financial markets. The participants also placed considerable focus on policy issues, identifying the nature and extent of possible market imperfections and impediments, and the scope for policy-makers to address these.

Robin Brooks’ paper on Demographic Change and Asset Prices:

finds little evidence to suggest that financial markets will suffer abrupt declines when the baby boomers retire. In fact, in countries where stock market participation is greatest, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US, evidence suggests that real financial asset prices may continue to rise as populations age, consistent with survey evidence that households continue to accumulate financial wealth well into old age and do little to run down their savings in retirement.

posted on 25 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Capitulation of the Cyclical US Dollar Bears: Doomsday Postponed (Again)

Even the cyclical US dollar bears are capitulating:

We have argued for more than two years now that the dollar is structurally sound, and the market’s fixation on using the dollar as the key tool of C/A adjustment is a fundamentally flawed notion, reflecting a lack of understanding of the effects of globalization. To us, outsized global imbalances are a logical consequence of globalization of the goods and the assets markets. We won’t repeat the details of our thesis on the dollar, but only stress that our call this year for the dollar to correct has been based purely on cyclical considerations. We are not sympathetic to the popular notion that the dollar ‘must’ correct sharply or crash, and that 2005 was a bear market rally in a secular dollar decline. This is why the changing cyclical outlook of the US and the global economies has such a major impact on the trajectory of the dollar…

As US inflation trends higher and global interest rates continue to rise, the dollar will be supported. The nominal short-term cash premium of the USD has reached 2.7%, and is still rising. We have long warned about the impact of the upside surprise in US inflation on the dollar and how it could alter our currency forecasts. We now believe that the cyclical dollar correction we had expected to take place in 2H this year may be further postponed to 4Q this year.

A recent IMF Working Paper sheds light on the structural underpinnings of the USD:

the presence of negative dollar risk premiums (i.e. expectations of a dollar depreciation net of interest rate effects) amid record capital inflows could suggest that investors may favor U.S. assets for structural reasons. One possible explanation could be that the Asian crisis created a large pool of savings searching for relatively riskless investment opportunities, which were provided by deep, liquid, and innovative U.S. financial markets with robust investor protection. Moreover, the continued attractiveness of U.S. financial markets to European investors suggests that they offer a large array of assets, with different risk/return characteristics, that facilitate the structuring of diversified investment portfolios. Looking forward, this suggests that the allocative efficiency of U.S. financial markets could mitigate risks of a disorderly unwinding of global current account imbalances.

posted on 22 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

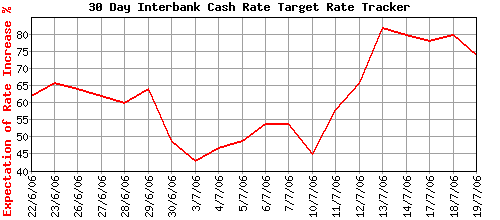

RBA Rate Hike Probabilities

The implied probability of a 25 bp tightening in the official cash rate to 6.00% at the RBA’s August meeting has firmed in the wake of last week’s strong June employment report, peaking at just over 80%, based on the August 30-day interbank futures contract.

posted on 20 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Economic Consequences of War in the Middle East

Kevin Hassett extrapolates from historical experience:

A 37 percent move up from $78, pushing even past $100, is certainly possible given past oil-price responses to war in the Middle East. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, oil prices increased by exactly that percentage during the course of the fighting…

Given that there are many signs the U.S. economy has already been slowing, such a surge in oil prices might well be enough to push the economy into a recession.

There is significant historical precedent. The 1956 war in Egypt shut the Suez Canal to oil tankers. Oil producers cut output by 1.7 million barrels a day, roughly a 10 percent decrease in world oil production. Prices surged, and by August 1957, we were formally in a recession.

The outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 caused world oil production to drop 7.2 percent. By July 1981, there was a recession. Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, and the same pattern held.

With that likelihood, expect the normal “flight-to-safety” assets to rally if full-scale war erupts. Gold prices would head way up, interest rates on government securities way down. During the 1982 Lebanon War, the 10-year Treasury bill rate dropped 12 percent in the 11 weeks from just before war began in early June to Aug. 24, 1982, the day after the PLO agreed to withdraw its forces.

The stock market would also take a big hit, history shows. During the course of the Suez Crisis in 1956, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index dropped 5 percent.

posted on 18 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

In Defence of Bernanke

James Surowiecki defends Ben Bernanke’s commitment to a more open communications style:

acknowledging uncertainty doesn’t play well with the media or the market. Today, the Fed’s actions are subject to constant press scrutiny. And it’s easier to lure audiences by using labels like “hawk” and “dove” than by exploring the subtleties of forecasting an uncertain future. In theory, investors should look past the headlines to the substance, but if the multitudes are treating the headlines as important news it’s hard for any individual investor not to do likewise.

John Taylor argues that recent Fed policy actions accord with his ‘Taylor principle:’

Since the beginning of Mr. Bernanke’s term, the Fed has responded by raising the funds rate by 75 basis points—to 5.25% from 4.5%, which is the neutral rate according to the St. Louis Fed’s version of the “Taylor rule.” This rise appears to be more than the increase in inflation since the start of his term; so, thus far, the Bernanke Fed is following a key principle of monetary success. There is likely to be some more work to do, however. If the inflation rate of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) continues at the 3.3% pace of the past 12 months, then a funds rate of 6.5% will be needed.

Oddly enough, Taylor opposes formal inflation targeting, even though an inflation target is implicit in his Taylor rule.

posted on 13 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 44 of 45 pages ‹ First < 42 43 44 45 >

|